Call numbers

I finally got some call numbers. Not for everything, but for a better portion than I thought I would: about 7,600 records, or c. 30% of my books.

The HathiTrust Bibliographic API is great. What a resource. There are a few odd tricks I had to put in to account for their integrating various catalogs together (Michigan call numbers are filed under MARC 050 (Library of Congress catalog), while California ones are filed under MARC 090 (local catalog), for instance, although they both seem to be basically an LCC scheme). But the openness is fantastic–you just plug in OCLC or LCCN identifiers into a url string to get an xml record. It’s possible to get a lot of OCLCs, in particular, by scraping Internet Archive pages. I haven’t yet found a good way to go the opposite direction, though: from a large number of specially chosen Hathi catalogue items to IA books.

This lets me get a slightly better grasp on what I have. First, a list of how many books I have for each headline LC letter:

A B C D E F G

83 693 65 1076 714 323 126

H J K L M N O P

401 171 35 271 37 138 1 2679

Q R S T U V Z

418 86 108 142 29 16 62

P is literature and criticism, which there’s a lot of. C, D, E and F are history, the latter two American; B is philosophy and religion, H is social sciences, Q is physical sciences, L is education, and nothing else (medicine, technology, etc—even “O,” which I don’t think exists) is over 200 books.

So what do we do with them? First, let’s make sure they look like they make sense on some old problems. How much do these classes use the word “evolution”?

Description Permille

Q SCIENCE 0.163

B PHILOSOPHY. PSYCHOLOGY. RELIGION 0.108

H SOCIAL SCIENCES 0.079

L EDUCATION 0.078

M MUSIC AND BOOKS ON MUSIC 0.077

O 0.045

R MEDICINE 0.041

U MILITARY SCIENCE 0.037

N FINE ARTS 0.035

Z BIBLIOGRAPHY. LIBRARY SCIENCE. 0.034

T TECHNOLOGY 0.034

0.031

J POLITICAL SCIENCE 0.030

V NAVAL SCIENCE 0.024

S AGRICULTURE 0.021

A GENERAL WORKS 0.020

C AUXILIARY SCIENCES OF HISTORY 0.016

G GEOGRAPHY. ANTHROPOLOGY. RECREATION 0.016

E HISTORY OF THE AMERICAS 0.009

P LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE 0.009

F HISTORY OF THE AMERICAS 0.008

D WORLD HISTORY 0.008

K LAW 0.003

Looks about right, although I wouldn’t have thought history or particularly anthropology would be quite so low. The numbers mean that, for instance, 0.16 out of every thousand words in science books are the word “evolution.” I can list the highest density subclasses:

> class.summary(“evolution”)[1:10,]

working on item number 1 of 1 (evolution)…

Description Permille

QH Natural history - Biology 0.783

HM Sociology (General) 0.533

JA Political science (General) 0.506

RB Pathology 0.329

BL Religions. Mythology. Rationalism 0.316

B PHILOSOPHY. PSYCHOLOGY. RELIGION 0.261

BD Speculative philosophy 0.238

RZ Other systems of medicine 0.214

BJ Ethics 0.201

QD Chemistry 0.188

Some of these classes are quite small, but the general numbers look about right. Sociology uses the word “evolution” almost a hundred times more frequently than American history. That’s a nice illustration of, though not a revelation about, the importance of evolutionary thought for some of the social sciences even compared to biology. Ethics is higher than I would have thought—I’ll have to correct my sampling functions so I can get text examples of just what that is.

How about more common words? Like the one I’m writing about?

> class.summary(“attention”,shorten=T)[1:10,]

Description Permille

L EDUCATION 0.429

R MEDICINE 0.292

M MUSIC AND BOOKS ON MUSIC 0.229

S AGRICULTURE 0.224

H SOCIAL SCIENCES 0.215

U MILITARY SCIENCE 0.214

B PHILOSOPHY. PSYCHOLOGY. RELIGION 0.211

E HISTORY OF THE AMERICAS 0.204

Z BIBLIOGRAPHY. LIBRARY SCIENCE. 0.188

C AUXILIARY SCIENCES OF HISTORY 0.184

I’m pleased about this, since I’m arguing a lot for the importance of existing educational discourses of attention shaping popular psychology in the 1920s and 30s. BF (Psychology) clocks in at .610. I need to look at the usage, but the prominence of music is good for that half-chapter I’ve been pitching on listening manuals. Mention doesn’t imply contestation, of course—I think the medical category is high because of diagnosis, and military may be just because of the drill word—but it’s not a bad proxy, as they go.

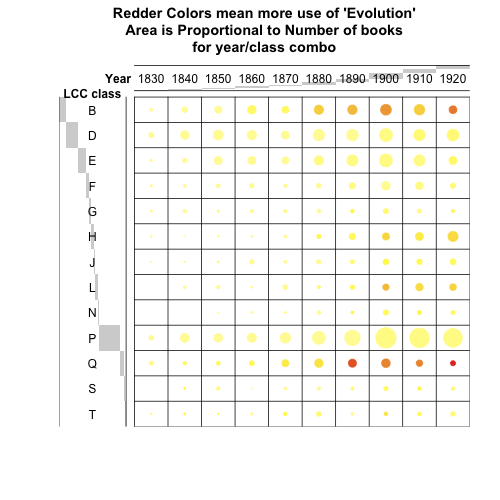

How do we bring the historical dimension back into all this? The numbers are very small for most of these categories, so I think it’s best just to dump some of them for now, and for others use a representation that reminds us just how little data we’re dealing with. If I keep categories with more than 50 or so books, we can get a balloon chart like so: (These aren’t decades, but rounded years–so 1876 and 1884 are with 1880, and 1885 and 1891 with 1890. I don’t like decades for the most part because I think they lead to stereotyping.)

But that’s not perfect: it’s good for communicating scale and the vagueness of frequency data, but it’s not really appropriate because there aren’t many words that will have historically interesting info in more than a few cells of the grid. The comparison with “Darwin” is interesting, because it highlights how the discourse of evolution spread outside the science more than it did Darwin’s name:

But that’s a lot of ink to expend on a table that doesn’t even make the numbers legible. I hate side-by-side bar charts, but using width to indicate number might not be bad here. I’ll have to think on it some more. I could see these being useful in some cases where you wanted to know just where a word was being used that had a flattish trend overall, and initially, they’re not bad for reminding what the distribution of books is. (It’s interesting to see that the history classes hardly increase at all from the 1860s. The social science and education classes (H and L) just get bigger and bigger, as do those novels in P.)

Also, since I haven’t said anything about source libraries for the google-scanned books: Why don’t I have call numbers for more than 30% of my books? Does the shortfall have to do with the libraries they come from? Here’s the percentage of my books that have call numbers, by the library IA thinks they came from (minus a few small ones):

| Library | Books | Percent |

+———————————–+—––+———+

So the Michigan and the Cal books are the best, and they’re some of the biggest partners in Hathi; and Harvard, only just recently a member of Hathi, is the worst. But it’s pretty even across the libraries–using internet archive data, library data alone can’t explain whether there’s call number data. Internet archive is partly to blame–they only have OCLC ids for about two thirds of the books I downloaded, and they don’t nicely integrate them into their downloadable catalogs. But the rest of the variation is odd–there are some gaps between IA’s holdings of books and what I can get.

Comments:

What does agriculture have to do with attention?!

Jamie - Dec 2, 2010

What does agriculture have to do with attention?!

I think it’s a use-mention thing—agriculture b…

Ben - Dec 4, 2010

I think it’s a use-mention thing—agriculture books are probably more instructive than other genres, so they do things like tell farmers to pay careful attention to signs of boll weevil infestation. That’s why, I suspect, medicine is so high as well. They’re not describing attentional disorders in the 19th century, they’re telling doctors to pay attention to symptoms in diagnosing other diseases. Or at least that’s what I’d guess, I still have to make my sentence sampler work on particular genre subsets.

I think it’s slightly more interesting than th…

Ben - Dec 4, 2010

I think it’s slightly more interesting than that, after looking at the texts: “Agriculture” also includes a _lot_ of books about hunting and fishing, and animals and fish are frequently described as having attention gained or diverted. Not all of it is like that, but maybe enough to explain the excess over normal. I like that a lot: I’m mostly interested in folk child psychology, but animal psychology adds an interesting dimension I’ve only thought about a little.