Capitalist lackeys

I’m interested in the ways different words are tied together. That’s sort of the universal feature of this project, so figuring out ways to find them would be useful. I already looked at some ways of finding interesting words for “scientific method,” but that was in the context of the related words as an endpoint of the analysis. I want to be able to automatically generate linked words, as well. I’m going to think through this staying on “capitalist” as the word of the day. Fair warning: this post is a rambler.

Earlier I looked at some sentences to conclude that language about capitalism has always had critics in the American press (more, Dan said in the comments, than some of the historiography might suggest). Can we find this by looking at numbers, rather than just random samples of text? Let’s start with a log-scale chart about what words get used in the same sentence as “capitalist” or “capitalists” between 1918 and 1922. (I’m going to just say capitalist, but my numbers include the plural too).

I put some difficult-to-read labels on the words there just to aid the understanding a little. Obviously the words themselves appear way more often than you’d think. Most of the rest of the common words are from the Left–class and labor in the upper right, down through workers and industry, proletariat, exploitation sticking out. That tells us a) socialist ideas were getting published in the popular presses, even if just to criticism them and b) Leftist critical words were the most uniquely associated with capitalism after the Russian revolution, the war, and all that. Now, this probably partly because a particular species of propagandist can cruise through his entire working vocabulary in just two or three sentences. In fact, the sorts of analyses I’m doing probably rely on some level of transparency of language, which is just what they were trying to exploit. But if we keep on our toes, that just adds another level to the interest in the changing language of capitalism. (It also makes it easier to filter them out, if we want). Let’s look at some other words to see whether the usage of capitalism really shifted. First, we can get a list of the words that appear most surprisingly often with capitalism; I’ll limit it to words that appear more than 10 times, omitting capitalism itself, because otherwise we get a lot of typos (although also some interesting names, like Haywood and Kautsky; both the domestic and the European socialisms are pretty well represented):

> sort(overrepresent[jointlocal>=10\],decreasing=T)\[3:7\]

proletarians expropriation entrepreneur proletariat proletarian

218.86380 203.48907 97.32086 96.03775 92.12624

\> sort(overrepresent\[jointlocal>=10],decreasing=T)[8:12]

capitalism workingmen laborer exploitation wageearners

83.77562 81.86075 80.99913 53.53651 52.52731

Proletarian appears 219 times more than it usually does in sentences with capitalism; wage-earners appears 52 times. Some of these words are pretty rare, so it might be more useful to limit ourselves to words that are at least as common as ‘ capitalist, ’ which appears 500 times in the four years:

> sort(overrepresent[jointgeneral>=500\],decreasing=T)\[3:7\]

proletariat capitalism workingmen laborer exploitation

96.03775 83.77562 81.86075 80.99913 53.53651

\> sort(overrepresent\[jointgeneral>=500],decreasing=T)[8:12]

marx socialists exploited laborers bourgeois

45.62303 39.39736 39.38942 38.53344 34.47561

Still with the Leftism. Let’s see how some of these terms stack up historically:

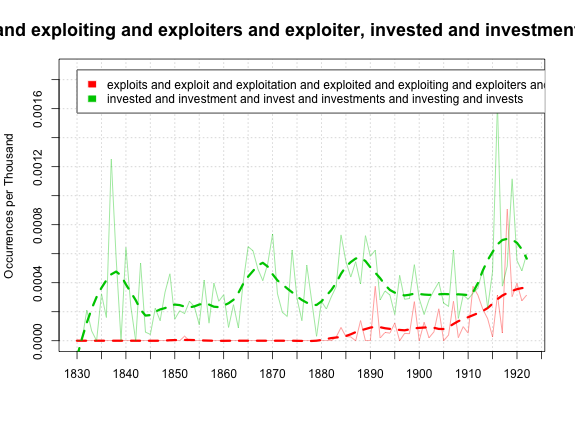

(Sorry for the awkward titles–I think it’s clear enough going on that I don’t have to muddle around in functions to change the titling schema to let me use these big bases of word stems.) These numbers are as a percentage of all words; that is, we’re basically charting the frequency in the language of sentences like “capitalists exploit tax loopholes” or “five capitalists invested $60 a piece.” So it seems like the language of exploitation does increase towards the end of the period, but not necessarily at the expense of more traditional words (although maybe ‘ investment ’ gathered a more negative valence over time).

Is there any way to get a general list of the most surprising words beyond just the list of very rare ones without setting an arbitrary cutoff? I’m out of my depth, here–I need to either read a book about nonlinear modeling, or start reading more widely in some of the computational linguistics stuff, or I don’t know what. But this blog is built on using loess curves in unjustifiable ways, so for the time being, I’ll just fit a loess curve to the log-log chart of a) times above normal a word appears, and b) the number of times it appears in the entire period to find things that really stick out from the chart. Loess accounts for the fact that it’s unsurprising there are some words that appear only a few times, and zooms in on the ones in the middle as really meaty: on the other hand, it assumes that words that appear about 10,000 will appear a little under average, which is certainly wrong.

The top twenty words are the red dots: here they are in order:

> names(sort(model$residuals,decreasing=T)[1:20])

[1] “laborer” “proletariat” “workers” “laborers” “socialist” “employer” “socialists” “class” “workingmen”“labor” “socialism” “industry” “capital” “exploitation” “profit” “production” “capitalism” “industrial”“profits” “employers”

So those are the words that appear disproportionately in a sentence with capitalism. If we do the words that appear disproprotionately in books with “capitalism”, it looks about the same. (Although the chart puts to rest any idea that loess is an acceptable way to model this data).

> names(sort(model$residuals,decreasing=T)[1:10])

[1] “laborer” “labor” “industrial” “socialist”

[5] “workers” “capital” “socialists” “industry”

[9] “laborers” “proletariat”

So, blithely ignoring my gross misuse of modeling methods, we get a couple lists that actually look vaguely reasonable. What do we get in the 1830s, by contrast?

For association by words, the socialist terms are mostly missing, replaced by a number of business terms. But based on the spellings and the examples I saw last time it seems like it’s pretty clear that the books that mentioned capitalism in the United States were mostly British, and already fixated on the relations to labor, which takes three of the top four and gives us a definite expected reading for what “proportion” and “wages”are being used for.

> names( sort(model$residuals,decreasing=T)[1:20])

[1] “labourer” “capital” “labourers” “labour”

[5] “proportion” “wages” “profits” “increase”

[9] “commodities” “profit” “diminished” “production”

[13] “diminution” “increased” “millions” “quantity”

[17] “rate” “expenditure” “share” “product”

But for books, the neat little system breaks down towards the end, as ‘ the ’ creeps on to the list. That just means the loess isn’t working perfectly.

> names(sort(model$residuals,decreasing=T)[1:20])

[1] “labourer” “labour” “money” “labourers”

[5] “labouring” “classes” “cent” “class”

[9] “income” “obtain” “capital” “trading”

[13] “security” “increase” “population” “profits”

[17] “diminished” “profit” “the” “per”

What I really need is some sort of Audobon field guide to distributions so I can get a better fit. Or really, to go read in the text mining literature, because this can’t be a new problem. Anyway, I think it might be working well enough to cluster out a little bit from a few words, at least.

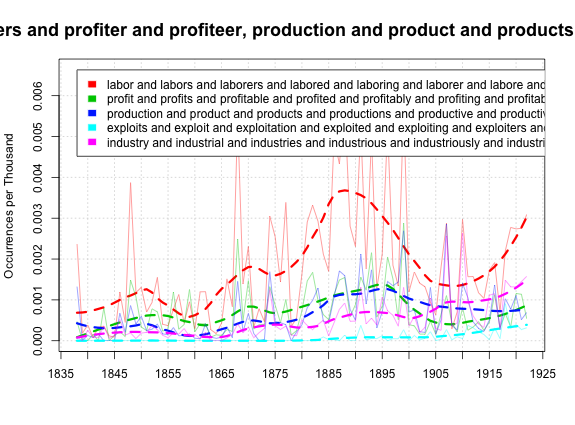

So one last chart: here are five of the major word-stem groups we got, plotted from 1838 to 1922. (There are a couple economics textbooks in 1837 that blow up the whole chart, so I’m just, unfairly, leaving them out). The labo(u)r connection is always the strongest in the language, but particularly so in the worst periods of strife, the 80s-90s and then after the war. Profit- drops away after 1895, which we’d need a little reading to explain; industr- rises steadily; and the language of exploitation only begins to tick up at the end.

Comments:

Matlab, eh? Wanna collaborate on some python tools?

Anonymous - Dec 0, 2010

Matlab, eh? Wanna collaborate on some python tools?

@Anonymous: I just saw this again. R, not Matlab. …

Ben - Jan 4, 2011

@Anonymous: I just saw this again. R, not Matlab. And I only know perl (‘ tools from the 90s… ’) If your anonymous self still exists, what do you think we need?

I popped by here basically to say for the record that TF-IDF, which I’ve been using lately, replaces all this nonsense about loess fitting to find associated words quite nicely, at least at the book level.