Generations vs. contexts

When I first thought about using digital texts to track shifts in language usage over time, the largest reliable repository of e-texts was Project Gutenberg. I quickly found out, though, that they didn’t have works for years, somewhat to my surprise. (It’s remarkable how much metadata holds this sort of work back, rather than data itself). They did, though, have one kind of year information: author birth dates. You can use those to create same type of charts of word use over time that people like me, the Victorian Books project, or the Culturomists have been doing, but in a different dimension: we can see how all the authors born in a year use language rather than looking at how books published in a year use language.

I’ve been using ‘ evolution ’ as my test phrase for a while now: but as you’ll see, it turns out to be a really interesting word for this kind of analysis. Maybe that’s just chance, but I think it might be a sort of indicative test case–generational shifts are particularly important for live intellectual issues, perhaps, compared to overall linguistic drift.

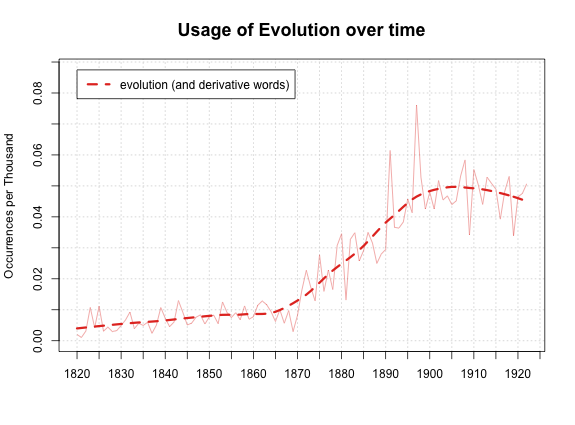

To start off, here’s a chart of the usage of the word “evolution” by share of words per year. There’s nothing new here yet, so this is merely a reminder:

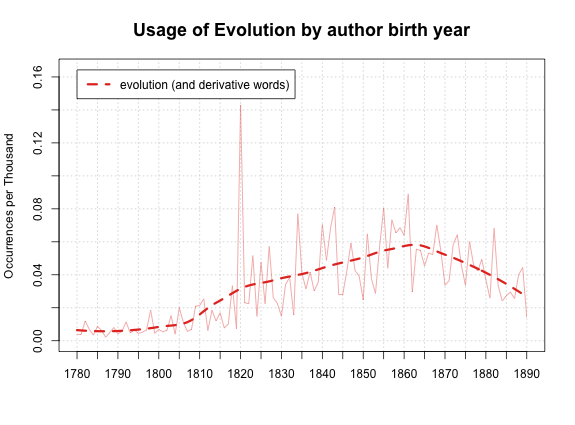

Here’s what’s new: we can also plot by year of author birth, which shows some interesting (if small) differences:

This shows us that authors born before about 1805 hardly use the word evolution at all, and then usage steadily climbs through authors born in 1860, after which it declines. The growth is over about 40 to 50 years, compared to about 30 years of growth to peak (1870 to 1900) for book publication date. The growth occurs on a larger scale even without the big peak in 1820 (which is, I can confirm, due to Herbert Spencer, one of the most frequent authors in my database. Darwin, by comparison, doesn’t move the chart at all in 1809).

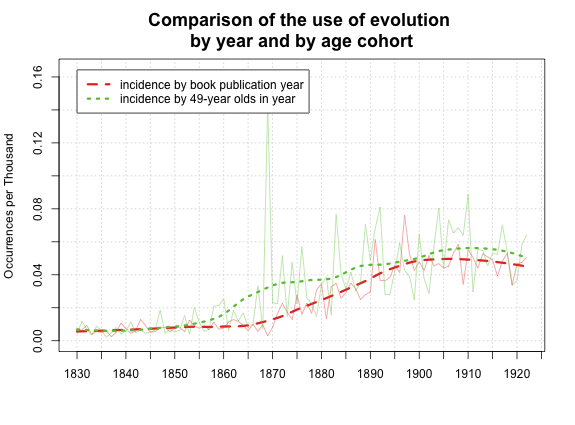

We have two different ways of looking at vocabulary usage: immediate context, and generational context. What’s the best way to compare them? Well, I found in my first post on author birth dates that the median age of authors when their books are published is about 49. To get a more direct comparison, we can look at the resemblance of these two curves by shifting the birth year forward by 49 years and plotting them together. This is a little bit of apples-to-oranges, but I think it’s a road somewhere interesting. By plotting it this way and expecting them to coincide, I’m implying an assumption that since books are written, on average, by 49-year-olds, the language choices of 49-year olds should be about the same as the dominant language in a given year.

In this case, that assumption is strikingly incorrect. Pretty obviously, in this case, 49-year-olds are ‘ ahead of the curve. ’ (That remains true even if I take Herbert Spencer, 49 in 1869, out of the sample). What does that mean, you ask? Me too. It means that people who were 49 in the 1870s, for instance, use the word “evolution” quite a bit even though it’s not very popular at the time period we’d think they’d write the most books. This probably means they are using it more in their 60s and 70s than we’d expect.

That’s not, on the surface, particularly surprising, because the word didn’t exist at all earlier–but it’s still potentially interesting for what it tells us about how the term entered the language. In some ways, for example, this seems very un-Kuhnian, on a generational level; the older generation just picks up the new language of evolution and runs with it, rather than being displaced by a new generation using new words. On the level of individuals, of course, Kuhn might be more right—this could be an interesting thing to check down the road—or all the old folks might be arguing against evolution.)

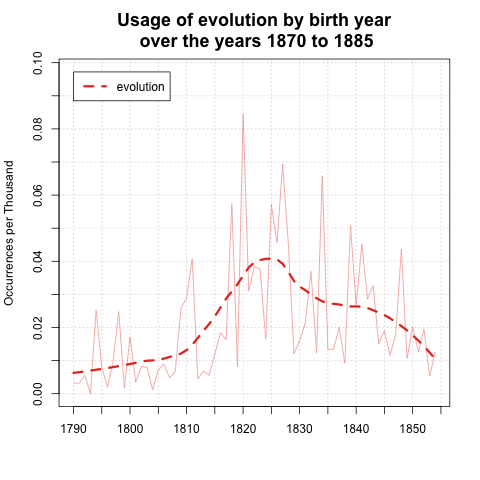

That chart shows generational use over full lifespans; what happens if we want to know just how different generations use the word “evolution” in a particular period of time? For instance, in the period 1870-1884, when the word really started to take hold, what age groups used it the most? Let’s take a look:

This should be a somewhat surprising chart, I think. It’s telling us that from 1870 to 1885, the heaviest users of the term “evolution” were not the young guns—the Civil War generation born in the 30s and 40s—but their slightly older peers. (I should confess I’ve cheated a bit to make my point–if I include 30-year olds in the sample, there’s a huge spike driven by a few books that skews off the whole chart. So it’s not as neat as it looks here. But this is accurate for 31- to 80-year-olds, and the high percentage by thirty-year-olds is partly driven by how few of them there are)

That’s weird, right? You’d think young people would use emerging words more than do old people, but that doesn’t seem to be the case here. On some level, we can explain this anecdotally—1810 is Asa Gray, 1820 is Spencer, 1825 is Huxley, etc. But that’s really more description than explanation—It shows us that it’s been staring us in the face in some ways that Darwinists are old, but thinking about it structurally puts it in a new light. (I didn’t know Gray was so old, for example, though this isn’t my field.)

Is “evolution” truly odd, or is this a trend? Well, doing principle components analysis I stumbled across a list of words that steadily increase their usage over the 19th century. Those tend be function words, not meaning-laden ones like evolution. So how do they compare? If I dump some of those onto an (ugly! R’s default colors aren’t great) chart, evolution really sticks out; the rest of them move around, but they tend to move upward over time, while evolution clearly has a bump among 50-60 year-olds that other words lack:

Now, those words all represent a particular sort of linguistic drift–the type that computers are great at noticing, and people terrible. A subtle increase in use of a word like “appreciation” instead of other synonyms is a shift in language that probably doesn’t represent a shift in ideas the way “evolution” does. The tailing off at the end of the period (in which there are few authors) seems perhaps less notable than it might have initially, and the almost complete lack of evolutionary language by anyone older than Darwin (b. 1809) himself jumps out a bit more. But that hump in the 1820s remains.

So far, I think this evidence suggests there might be something interesting about evolution’s adoption in the USA being driven largely by a somewhat older generation. But to be sure, maybe we should put some other words in the mix that are more similar to evolution. First, let’s look at directly connected words:

Here, we see some similar spikes in the 1820s for “Darwin” and “species”, and perhaps selection, but the more notable feature are the spikes for those words around 1809-1810 as well; that’s the Darwin-Gray generation, and they seem to be more interested in the biological/scientific discourse than the 1820s generation who (to wildly speculate) might be branching “evolution” out more into the realm of the social, etc. To look into this further, I could do a correlation chart by birth year to see how different generations use Darwinism differently, just as I saw how “heredity” and evolution became less heavily correlated from 1860 to 1880.

A final question, moving forward: is evolution driven by this type of old adoption curve because of something about science/technology? Let’s look at some other words that have to do with technological adoption in the same period to get a sense.

‘ Steel ’ and ‘ telegraph ’ show a basically steadily ascent, but ‘ railroad ’ is actually similar to evolution in some ways–it has a founding generation in the 1800s that uses it quite heavily, after which it falls off before beginning a new rise.

There’s a lot of interesting stuff here, and I’m not actually sure which threads to chase down at the moment. One thing that seems clear is that the noise on this data is considerably louder when I try to break down birth-years over just a fifteen-year span–I’m reduced to using only 3 or 4 thousand books for some of these charts, which may not be enough. Some of this stuff about evolution is suggestive, but the numbers aren’t big enough to tell us much more than that. Still, there may be ways to ask some interesting general questions about how different words and different types of words differ in their age-adoption patterns, which is what I’m thinking about doing next.