Graphing word trends inside genres

Genre information is important and interesting. Using the smaller of my two book databases, I can get some pretty good genre information about some fields I’m interested in for my dissertation by using the Library of Congress classifications for the books. I’m going to start with the difference between psychology and philosophy. I’ve already got some more interesting stuff than these basic charts, but I think a constrained comparison like this should be somewhat more clear.

Most people know that psychology emerged out of philosophy, becoming a more scientific or experimental study of the mind sometime in the second half of the 19C. The process of discipline formation is interesting, well studied, and clearly connected to the vocabulary used. Given that, there should be something for lexical statistics in it. Also, there’s something neatly meta about using the split of a ‘ scientific ’ discipline off of a humanities one, since some rhetoric in or around the digital humanities promises a bit more rigor in our analysis by using numbers. So what are the actual differences we can find?

Let me start by just introducing these charts with a simple one. How much do the two fields talk about “truth?”

These charts look the same as the ones I’ve been making before. “Truth” at the top means I’m looking at the word “truth,” while the colors indicate not words but different library sections. I’ve put in the number of books in each field as “n”, because we’re dealing with numbers so small that a few books can really change the chart flow. It’s worth looking at them so we don’t get too excited about a few outlier years.

This chart is telling us that about .7 out of every thousand words in psychology and philosophy, respectively, were “truth” in the 1850s. That number went up slightly for philosophy, and declined a bit in psychology. “Truth,” of course, is subject to massive use-mention problems in this context: surely philosophers actually talk about truth, while psychologists are probably more likely to merely assert the truth of their theories. But with some more research, this might not be a bad illustration of someone’s theory about the increasing epistemological security of psychology over the period. (Or it might indicate a lack of belief in absolutes, which is how Dan Cohen provisionally interpreted “truth” charts for the Victorian books project, but I’m not sure I buy that with regards to usage in texts, rather than in book titles.)

On to more particular words. Wikipedia tells us “Psychology was a branch of philosophy until 1879, when psychology developed as an independent scientific discipline in Germany and the United States,” which is rather cheerily definite. One of the things I find these charts actually quite helpful for is that they generally tend to reinforce the lack of willingness of intellectual historians to seize fast and firm to dates. So for example, one way to measure the distinction of the genres is by actually using the word “psychology” to discriminate between them. It’s always been a word–but when does it start showing up in books classified as psychology?

So even the books classed* as psychology don’t actually use the word more than philosophy books until the second half of the 1880s. Naming something is a very important way of setting it apart–and by this, psychology didn’t really get going until around 1887. But it was quick once it happens–there’s no slow ascent here. (The smooth upward curve on the loess trend line is deceptive, I think, but given the jumpiness of the year-by-year we need some smoothing. I prefer loess to moving averages on messy data like I have, but I leave the year-by-year fluctuations to keep me honest.)

*[One thing that’s worth remembering is that LC classifications are themselves a historical artifact, created from 1895 to 1940 or so. So all those books from the 1880s weren’t actually classed as psychology at the time; it happened later. (In some cases, much later, only when Ann Arbor or wherever acquired a copy of the book). I’ve been pleased that that history actually makes LC classes particularly good for just the period we have the most public domain books for: the various differences in the Hs between sociology, social reform, and the family make much more sense on late 19C books than they do on modern books in a lot of ways. If you don’t study the late 19C United States, though, LC classes are probably more frustrating than interesting.]

What are some other things that might distinguish psychology and philosophy? There’s surely going to be something about science:

…but that doesn’t seem to be it.

Nothing more distinguishing between the two here, either. Although that tandem spike after 1870 is fascinating, because it highlights the way that secular changes in language can take place across genres. Other changes (like the rise of “psychology”) take place because some genres use a word more. And yet other changes occur when different genres stay constant, but one gets more predominant than the other. These all have radically different implications for how we interpret lexical statistics, and I want to investigate them later in some depth. So let me just flag that for now.

Anyway, one solution to philosophy vs. psychology is that we remember that “science” itself isn’t the keyword the early psychologists use, but rather “experiment.”

I wouldn’t read too much into the early peak (small samples, remember), but it’s worth noting that the far greater presence of “experimental” starts well before Wundt sets up his Leipzig lab in 1879. That is to say, Wikipedia’s hard line isn’t quite right. I have to fix my program to get text examples to work with the new database, but something interesting is going on here. Throwing in a bunch of names in early psychophysics and physiology as a combined category doesn’t explain it any better…

…although it does neatly illustrate the passing away of the importance of that founding generation over time in their own discipline. (And also it shows off that all 6 of those fairly obscure names show up in my list of the 200,000 most common English words–there’s really hardly anything the shortcut loses.) Maybe it’s the genre issue again?

Within this set, it’s tempting to just plug in any word I can think of. Let’s plug “evolution” and a couple related words in, since I test “evolution” on everything.

“Scientific” psychology is earlier on to to the evolution train, but by the end of the period philosophy is just as occupied with evolutionary language. We know Dewey is a philosopher of evolution, but he’s perhaps not really at the vanguard here the way he’s sometimes, I think, portrayed (link to a book I haven’t read). In fact, there’s a fairly strong evolutionary current in a lot of philosophy by the time the 20C rolls around. Some of this is surely Fiske and Spencer and their ilk as well, filed as philosophy rather than sociology or whatever we’d consider it today. What this really reinforces for me, though, is that I really have to build my connections to the text back in.

The Darwin chart is even weirder, because it again shows hardly any difference between the fields, except for maybe a small head start in the pre-Wundtian psychology. Both even share a dip that might correlate with the eclipse of Darwinism Hank and I talked about earlier:

The real answer, of course, is not to just plug in words that we find interesting—although sometimes that will be good—but to use some more sophisticated tools to find the differences between the corpuses with a much larger set of words. Something sort of like I was doing with words that have disproportionate ties to other ones. Maybe I’ll get to that soon.

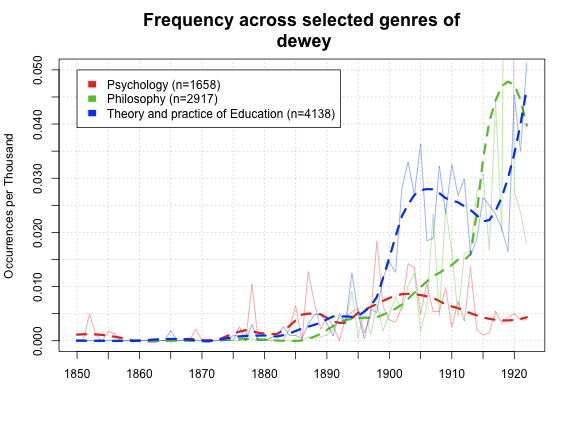

There’s a lot more that could be done with that sort of scientific vocabulary, but I want to finish up here for now by looking at just one name. To do better work here, I’d have to load up some bigrams–James and Hall both have too common names to search for, and Melville “Decimal system” Dewey clouds the water for John. (If only he’d gone by “Melvil Dui” more consistently.) But it’s still interesting to take a couple. I’m going to throw in another LC class here, too: LB, theory and practice of education. It should be clear why:

Isn’t that a nice image of the career of John Dewey?** He starts out most prominent in psychology in the 80s (1878 is a false positive, I think), then is propelled into education (along with Melvil, alas), and only after that starts to really work his way into the philosophy literature.And his decline in psychology after 1905 shows the eclipse of that founding generation and the move to a more rigorous but less open and speculative field. It’s education and philosophy where he really continues his work. In some ways, that puts the lie to the idea that psychology truly split off from philosophy in a one way street–this chart shows the ways they continued to interchange with each other (and with education, a related field: not many other people are interest in Edward Lee Thorndike or GS Hall, but they have charts that tell related stories I could go on about).

**[A nice image of Dewey’s career, that is, aside from the massive spike in 1919 I’ve left off the top of the chart. It’s probably some sort of artifact–maybe a catalog that lists hundreds of Dewey Decimal numbers, for instance. That’s why I like loess smoothing instead of moving averages, it takes those peaks a little less seriously.]

Comments:

Ben: Finally getting around to reading this, and I…

Hank - Feb 6, 2011

Ben: Finally getting around to reading this, and I’m loving it of course. I have a few thoughts:

Would you elaborate, for a few lines (in the comments, or in a new post) on what you mean by: “I really have to build my connections to the text back in”? Thanks, since this seems crucial.

Could you also elaborate on how you’re going to get Melvil out of there (if you can, somehow), and how you can add James and Hall in without noise? I just want a demi-technical explanation..

Request: would you do method or “scientific method” across the three genre classes you close with? This is for me, to be sure, but maybe it’ll produce an interesting result…

Thanks! More soon..

Thanks, Hank. Point by point: 1) I had some code …

Ben - Feb 6, 2011

Thanks, Hank. Point by point:

I had some code running that let me get usage samples in the flat text files to get a sense of the context a word has. I broke that when I upgraded my system, and haven’t put it back in yet.

Nothing fancy, just toss in some multi-name searches (“John Dewey”, “William James”).

Yes, but you may have to remind me later.