Making and publishing history in the Civil War

A follow up on my post from yesterday about whether there’s more history published in times of revolution. I was saying that I thought the dataset Google uses must be counting documents of historical importance as history: because libraries tend to shelve in a way that conflates things that are about history and things that are history.

I realized after posting that the first of the two graphs in Michael Witmore and Robin Valenza’s post actually shows a spike in publications of US history somewhere near 1860. (It actually looks closer to the late 1850s, but there aren’t any grid lines on the chart.) Bookworm is pretty much useless in the 17th century, but it’s on solid ground in the 1860s. And I’ve long known there was something funny going in Bookworm around the Civil War, particularly in the History class.

So–is there more history published in the Civil War period in the Bookworm database? What kind?

This chart is comparable to the one that Google made, but with fewer lines and without any aggregation. It shows four LC classifications from 1850 to 1870 by number of books. (It’s LC classifications–stack location–not subject headings, that the original post appears to use.)

You can create pretty much this same chart in Bookworm by searching for the word ‘ a ’; clicking on the lines around 1860s shows what the books are. Quite a number are things like the “Lincoln Catechism”, an election-year grabbag of racial innuendo and hard-currency absolutism:

Does the Republican party intend to change the name of the United States?

It does.

What do they intend to call it?

New Africa.

Not only is this not history–it’s so ephemeral that it probably wouldn’t have made it into the collection if it were about a less interesting historical period–Grover Cleveland’s black baby, say.

If you click around on Bookworm, you’ll find a lot more like this.

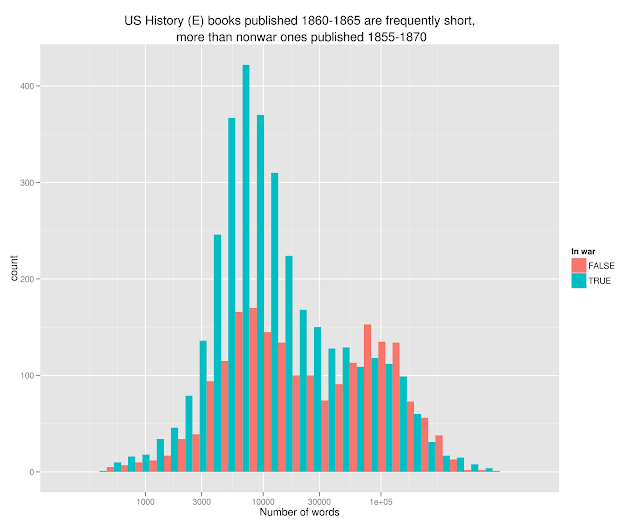

Having done that myself, I note one distinguishing feature of these ephemera: many are quite short, while real works of history tend to be fairly long. Looking at the lengths of the books confirms that the lengths of only E (US history) drops significantly in the 1860s:

And if we look at a log-scale histogram of book lengths comparing 1860-1865 book lengths to 1855-59 and 1866-70 lengths, we see an interesting pattern. In the non-wartime books, there are two nice peaks around 100,000 and 10,000 words; but in the war, the single peak at 10,000 words is much larger.

Some short books are still history–indeed, short books is probably how you’d respond to an increase in demand. But given the actual texts that Bookworm shows.

The question then is: does this same pattern apply to the 18th and 17th century historiography spikes?

One thing I’d note: a lot of the ephemera in Bookworm come from non-Google scanning projects: the Sloan-funded digitization at the Library of Congress, particularly, and other random sources. (The Lincoln catechism is from “the Friends of the Lincoln Financial Collection in Indiana.”) In other words, not the University libraries that Google digitized.

That’s significant because it suggests how difficult it is to count a ‘ book ’ at the margins–a lot of the Google estimates about the ‘ total number of books ever published ’ seem to rely on catalog metadata. But while university libraries tend to be fairly regular in their collecting patterns, special collections libraries tend to have much stranger bulges that reflect particular areas of interest–bequests from private collections, places they went on the auction market, dull campaign literature they didn’t misplace in the 1870s.

My general solution to this is to say that actually, we don’t want all the books ever published–we just want library books to analyze. (If we’re going to analyze any set as a whole). Partially because those books are interesting in themselves–built to last, probably better written and more intrinsically interesting–but also because the historical fact of their preservation, not their innate qualities, tells us a lot about the slice of society–librarians, educators, and their donors–who take it upon themselves to preserve books.

Comments:

Your penultimate paragraph drops off just when it …

John Russell - Jul 4, 2012

Your penultimate paragraph drops off just when it gets interesting.

How embarrassing. Editing to say that what’s u…

Ben - Jul 4, 2012

How embarrassing. Editing to say that what’s useful is that their preservation is what’s interesting, not their innate qualities.

Absolutely. Witmore and Valenza’s spike around…

John Russell - Jul 4, 2012

Absolutely. Witmore and Valenza’s spike around revolutions may be telling a story about what our libraries have valued over time more than anything about the revolutionary periods themselves.

Here’s an example for the English Civil War (u…

John Russell - Jul 5, 2012

Here’s an example for the English Civil War (using Michigan’s catalog):

http://mirlyn.lib.umich.edu/Record/005668828

General pamphlet, classed in DA with a whole bunch of other pamphlets (collection record: http://mirlyn.lib.umich.edu/Record/000239399). Most of these are current events, but will get classed in history. Your original point, obviously, but I wanted to come up with a concrete example.

And you are also correct that the original post/graph is using LC classification not LC subject headings.

Unknown - Jul 6, 2012

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.