Taylor vs. Darwin

Let’s start with just some of the basic wordcount results. Dan Cohen posted some similar things for the Victorian period on his blog, and used the numbers mostly to test hypotheses about change over time. I can give you a lot more like that (I confirmed for someone, though not as neatly as he’d probably like, that ‘ business ’ became a much more prevalent word through the 19C). But as Cohen implies, such charts can be cooler than they are illuminating.

But you can get into some interesting analysis even just at the wordcount level. Look at this chart (sorry if it’s small):

The red line is the frequency of the word ‘ evolution ’; the green one, ‘ efficiency. ’ (I’ll put a post at some point on how to read these graphs better.) Each one of those terms gets a week in your typical intellectual history survey, and each one has a canonical author associated with it. (If you’re a little fuzzy, Darwin’s Origin of the Species is 1859; Taylor’s Scientific Management is 1911, Shop Management 1903). And sure enough, both climb out of the ocean of insignificant words around the time we’d expect them to.

But look at the differences between the two. “Evolution” starts its climb shortly after Darwin publishes (the real spike in the data seems to be 1864, which gives Americans a chance to make it through that book), and rises in prominence for decades. “Efficiency,” on the other hand, increases in prominence five times in the first fifteen years of the century, before leveling off a bit. Taylor’s most famous work is at middle of the curve, and his first one is part of the rise, not before it. Both words show a major addition to shared cultural vocabulary, but the way they are taken in shows they are two very different intellectual movements.

The tools in hand can help us understand that change on both the micro and macro level. The macro questions are about the nature of trends–are there ways besides ‘ slope ’ of describing the differences between the two? What other words show the same sorts of patterns? Offhand, the evolution curve looks more the ones I see for technologies, while the efficiency curve resembles news events. Are there useful generalizations about different sorts of patterns of reception we could make? That may be a sociological questions, but here’s a more historical one: Is the change in adoption rate of new terms between the 1860s and 1910s actually reflective of changes in print culture itself, and could that be demonstrated from the data?

In the specific cases, more textual analysis can help disentangle what exactly was involved in that long rise of evolution and the meteoric one of efficiency. There’s a lot more to be said here, so I may save it for a future post, but what if we dig into the charts further for some subsidiary keywords about evolution to see how they fare?

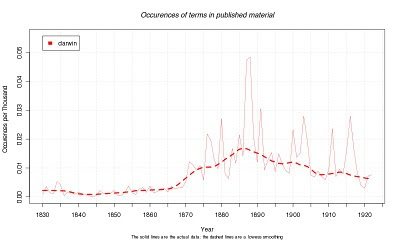

Darwin himself starts to become a household name five years after “evolution” begins its rise, but his prominence peaks (spectacularly) in the late 80s, before he begins his decline. It’s interesting to note that ‘ evolution ’ has a mini-decline of its own, but a decade and a half later–it keeps spreading for years while disembodied from its creator.

“Fittest” is a rare enough word on its own that we can clearly see the post-origin bump, although it declines from around the same period.

And what about Spencer? It’s a more common name, but we can see the same pattern–gradual rise, peak around 1878, moderate decline. (Incidentally, I think the similarity in these graphs goes some way towards justifying using lowess curves to smooth out the year-to-year fluctuations–the solid lines for these are hard to read, but the similarities in the trends are really striking. Spencer peaks just a bit later than Darwin–is that what you’d expect?).

And what about Spencer? It’s a more common name, but we can see the same pattern–gradual rise, peak around 1878, moderate decline. (Incidentally, I think the similarity in these graphs goes some way towards justifying using lowess curves to smooth out the year-to-year fluctuations–the solid lines for these are hard to read, but the similarities in the trends are really striking. Spencer peaks just a bit later than Darwin–is that what you’d expect?). So what does keep rising with evolution? Are there terms other than “survival of the fittest” we should check? I think wading into the historiography here might actually be an interesting litmus test to see what sort of specific applications we could come up with. The role of natural selection in US intellectual history is a pretty mature debate–but maybe we can more effectively illustrate what we know than broad pronouncements about Spencer vs. Darwin, or show some elements of the received wisdom that don’t track the numbers. That lull in evolutionary writing in the 1890s, for instance, is fascinating–is there a ready-to-hand, conventional explanation for that?

So what does keep rising with evolution? Are there terms other than “survival of the fittest” we should check? I think wading into the historiography here might actually be an interesting litmus test to see what sort of specific applications we could come up with. The role of natural selection in US intellectual history is a pretty mature debate–but maybe we can more effectively illustrate what we know than broad pronouncements about Spencer vs. Darwin, or show some elements of the received wisdom that don’t track the numbers. That lull in evolutionary writing in the 1890s, for instance, is fascinating–is there a ready-to-hand, conventional explanation for that?

Comments:

1. Lull in 1890s = “Eclipse of Darwinism,&quo…

Anonymous - Nov 6, 2010

Lull in 1890s = “Eclipse of Darwinism,” rise or prominence of neo-Lamarckians and saltationism and kooky discussions of hereditary mechanisms?

Here’s another word to look up - esp. from 1890 to 1923 - “culture.”

Hank