Treating texts as individuals vs. lumping them together

Ted Underwood has been talking up the advantages of the Mann-Whitney test over Dunning’s Log-likelihood, which is currently more widely used. I’m having trouble getting M-W running on large numbers of texts as quickly as I’d like, but I’d say that his basic contention–that Dunning log-likelihood is frequently not the best method–is definitely true, and there’s a lot to like about rank-ordering tests.

Before I say anything about the specifics, though, I want to make a more general point first, about how we think about comparing groups of texts.The most important difference between these two tests rests on a much bigger question about how to treat the two corpuses we want to compare.

Are they a single long text? Or are they a collection of shorter texts, which have common elements we wish to uncover? This is a central concern for anyone who wants to algorithmically look at texts: how far can we can ignore the traditional limits between texts and create what are, essentially, new documents to be analyzed? There are extremely strong reasons to think of texts in each of these ways.

The reason to think of many shorter texts are more obvious. In general, that seems to correspond better with the real world; in my case, for example, I am looking a hundreds of books, not simply two corpuses; any divisions I introduce are imperfect. If one book is a novel with a character named Jack, “Jack” may appear hundreds of times in the second corpus; it would be vastly over-represented. That knowledge, though, doesn’t lead us to any useful knowledge about the second corpus–there’s nothing distinctively ‘ Jack ’-y about all the other books in it.

Now, the presumption that every document in a set actually stands on its own is quite frequently misplaced. Books frequently have chapters with separate authors, introductions, extended quotations. For instance: Dubliners will be more strongly characterized by the 30 times the word “Henchy” appears than the 29 times “Dublin” appears, even though Henchy appears only in “Ivy Day in the Committee Room” and “Dublin” is much more evenly distributed across the set, since “Dublin” is a more common word in general.

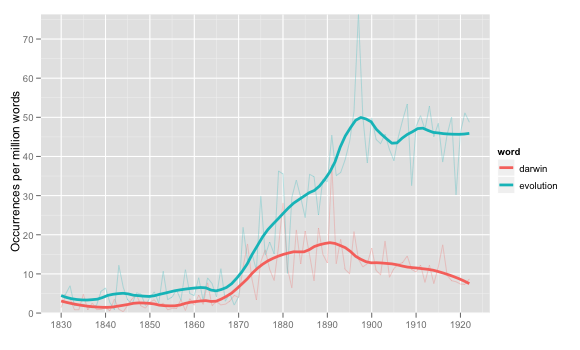

Even if we could create text-bins of just the right size, we wouldn’t always want to do so, though. There are lots of occasions where it makes a lot of intuitive sense to group texts together as one large group. Year-ratio counts is one. Over the summer, I was talking about the best way to graph ratios per year, and settled on something that looked roughly like this:

This is roughly the same as the ngrams or bookworm charts, but with a smoothing curve.

If you think about it, though, what’s presented as a trend line in all these charts is actually linking data points that consist of massively concatenated texts for each of the years. That spike for evolution in 1877 is possibly due to just one book–it makes us think something’s happening in the culture, when it’s really just one book again–the Jack/Henchy problem all over again? Instead of umping the individual years together, why don’t we just create smoothing lines over all the books published as individual data points?

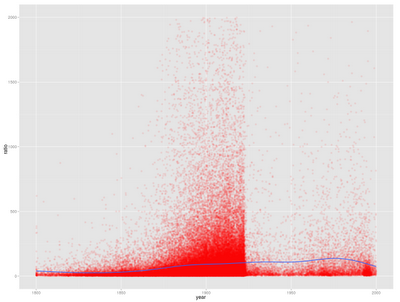

Well, partly, it’s just too much information:

Giving each book as a point doesn’t really communicate anything more, and we get _less_ sense of the year to year variability than with the more abstract chart. That’s not to say there aren’t advantages to be gained here (it’s good to get a reminder of just how many more books there are from 1890-1922, for instance), and I do think some distributional statistics might be better than the moving average for a lot of the work we’re doing. But it also takes an order of magnitude or two longer to calculate, which is a real problem; and it’s much easier to communicate what a concept like ‘ percentage of all words in that year ’ means than ‘ expected value from a fitted beta distribution of counts for all books in that year ’, even if the latter might be closer to what we’re actually trying to measure.

There are other cases where the idea of a text breaks down–with rare words, for instance, or extremely short texts. I’d love to just be able to use the median ratio percentage instead of the mean from the chart above; but since 3/4 of all books never use the word evolution at all, we won’t get much use out of that. With much rarer words or terms–which we are often very interested in–lots of useful tools will break down entirely.

How does this connect to these specific comparison algorithms?

The Dunning log-likelihood test treats a corpus exactly the same as it treats a document. There is both computational and philosophical simplicity in this approach. It lets us radically simplify texts across multiple dimensions, and think abstractly about corporate authorship across whatever dimension we choose. I could compare Howells to Dickens on exactly the same metric I could compare LC classification E to LC classification F; the document is longer, but the comparison is the same. But it suffers that Jack-

The Mann-Whitney test, on the other hand, requires both corpus and document levels. By virtue of this, it can be much more sophisticated; it can also, though, be much more restricted in its application. It also takes considerably more computing power to calculate. It *might* be possible to include some sort of Dunning comparisons in Bookworm using the current infrastructure, but Mann-Whitney tests are almost certainly a bridge too far. (Not to get too technical–but basically, Mann-Whitney requires you to load up an manipulate the entire list of books and counts for each word, sort it, and look at those lists, while Dunning lets you just scan through and add up the words as you find them; this is a lot simpler. I don’t have too much trouble doing Dunning Tests on tens of thousands of books in a few minutes, but the Mann-Whitney tests get very cumbersome beyond a few hundred.)

Mann-Whitney also requires that you have a lot of texts, and that your words appear across a lot of books; if you compared all the copies of Time magazine from 1950 to the present to all the phone books in that period, it would conclude that “Clinton” was a phone book word, not a news word, since Bill and Hillary don’t show up until late in the picture.

So when is each one appropriate? This strikes me as just the sort of rule of thumb that we need and don’t have to make corpus comparison more useful for humanists. Maybe I can get into this more later, but it seems like the relative strengths are something like this:

Dunning:

Very large corpuses (because of memory limitations)

Very small corpuses (only a few documents)

Rare words expected to distinguish corpuses (for instance, key names that may appear in a minority of documents in the distinguishing corpus).

Very short documents

Limited Computational resources

Mann-Whitney:

Medium-sized corpuses (hundreds of documents)

Fairly common distinguishing words (appearing in most books in the corpus they are supposed to distinguish)

Fairly long documents

Also worth noting:

TF-IDF:

Similar strengths to Dunning, but works with a single baseline set composed of many (probably hundreds, at least) documents used with multiple comparison sets.

Comments:

My name is April, and I am a student in a digital …

April - Apr 6, 2012

My name is April, and I am a student in a digital humanities seminar called “Hamlet in the Humanities Lab” at the University of Calgary: .

In my final paper for the course, I would like to base my argument on your blog post. You can read my paper after April 25th on the course blog: