Women in the libraries

It’s pretty obvious that one of the many problems in studying history by relying on the print record is that writers of books are disproportionately male.

Data can give some structure to this view. Not in the complicated, archival-silences filling way–that’s important, but hard–but just in the most basic sense. How many women were writing books? Do projects on big digital archives only answer, as Katherine Harris asks, “how do men write?” Where were gender barriers strongest, and where weakest? Once we know these sorts of things, it’s easy to do what historians do: read against the grain of archives. It doesn’t matter if they’re digital or not.

One of the nice things about having author gender in Bookworm is that it opens a new way to give rough answers to these questions. Gendered patterns of authorship vary according to social spaces, according to time, according to geography: a lot of the time, the most interesting distinctions are comparative, not absolute. Anecdotal data is a terrible way to understand comparative levels of exclusion; being able to see rates across different types of books adds a lot to the picture.

In this post, I’m going to run through a lot of basic metadata about the gender composition of libraries very quickly, because I need to know it to work with this data. Although this is the bookworm database, the rules for inclusion in Bookworm are so simple (Open Library page, Internet Archive downloadable file) that at least up to 1922, the results here should be broadly similar to any large selection of texts that draws heavily from the Google library-scanning project. (Most notably: HathiTrust and Google Books). And those are so similar to the composition of the university libraries that humanists have been using for decades, that even non-digital researchers should have some use for similar statistics.

More interesting findings might come out of more complicated questions about interrelations among all these patterns: lots of questions are relatively easy to answer with the data at hand. (If you want to download it, it’s temporarily here. For entertainment purposes only, etc., etc.)

The most basic question is: what percentage of books are by women? How did that change? (Of course, we could flip this and ask it about men–this data analysis is going to be clearer if we treat women as the exceptional group). Here’s a basic estimate: as the chart says, post-1922 results are unreliable. The takeaway: something like 5% at midcentury, up to about 15% by the 1920s.

Although the fall around 1950 is hard to interpret since the sample gets so small and specific, I do think it’s interesting: I think, without references that a lot of other indicators of women’s empowerment (Ph.D. and BA earning rates? age at first marriage?) show a similar pattern when plotted against time. Just another reminder that the 1960s are one of the least typical periods in US history, and that the widespread practice of using them as some sort of baseline is very misguided.

From now on, I’m removing post-1922 data from the analysis.

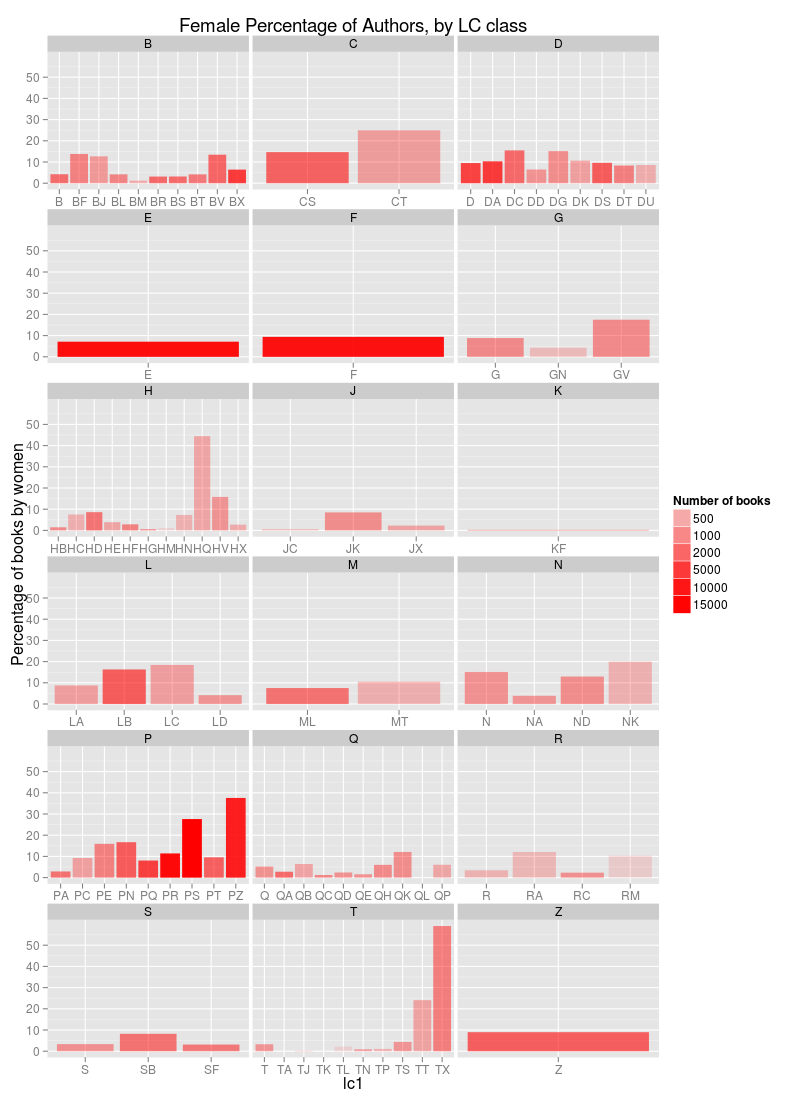

Next: Library of Congress classifications, my favorite proxy for genre. The labels won’t fit on this chart, but you can read them here. The results are generally between 10 and 20% female for most genres (roughly comparable to the data in the Arxiv nowadays, I think), with some notable exceptions.

(If it’s not clear: the transparency here is according to the (log of the) number of books in the category. There’s will be a strong tendency on these charts to overestimate the importance of some small genres: this is my attempt to let you avoid that).

The Ps–fiction–are far and away the most frequently female fields. There’s really no question about it: particularly PZ (“fiction and juvenile belles-lettres), but also PS (American literature) are more female than almost any other field.

DD, German history, is _far_ more male_dominated than any other field in history except maybe E, one of the two for US history. Does this reflect greater constraints on access to print in the heavily university-dominated German system in the 19C? (For American or German authors–the Ph.D.s are probably all going through Berlin, anyway). Are there other places that institutional discrimination might be evident?

Genealogy and particularly biography, (“CT”) are a really striking area of female authorship. Might be worth looking into.

HQ–“The Family–Marriage–Women” is about 45% female. Most of this is probably settlement-house stuff that is well covered in the historiography, but is nonetheless a little higher than I might have thought.

K, the law, has fewer women than anywhere. As with the German history, that can reflect the role of higher education in enforcing discriminatory practices.

The religion section of the B’s, BL-BX, is particularly male-dominated, with the exception of practical theology. The really strikingly low bar, BM, is “Judaism.”

From the number of authors I’ve worked with myself, I think of the Ls–education–as having a very high female percentage. (Although more in the 1930s than the 1900s). But though they’re a little higher, it’s not that notable.

The Ns, visual art, are a little more female than most other fields.

The low numbers in the sciences and technology are not very surprising; the spikes in the Ts are for handicrafts and home economics. The latter of those is the only field to break 50% female.

What about geography?

By state. Massachusetts does extremely well: of books with a publishing industry to speak of, only California does better. New York is OK, but in the middle of the pack. A lot of this probably has to do with the individual presses in the state–see the publishers list below for more on that.

A question emerges: Montana and Nevada both seem to have high female percentages. We know that western states had women’s suffrage early; is the same true of female authors? A map loses the information about which states actually have significant numbers of books published in them, but makes regional comparisons easier. My opinion is that it puts to rest any idea of a particularly progressive West, but I could be dissuaded from that.

International comparisons are interesting as well. We can look at publication country. The result is a really striking win for the United States, with almost 18% of books written by women. The Swedes are next, followed by the Australians. Once again, the Germans are shockingly bad. This seems too strong to be merely a genre effect: the Germany overall percentage is lower than a lot of the science fields are. What’s different about 19th century Germany compared to these other countries? And what does America not have? I’m strongly inclined to blame the developed system of universities.

Publishers exist in the data, although they’re a little harder to pull out. After a little text scrubbing (to make “Little,Brown” the same as “Little Brown” the same as “Little, Brown & co.”) the following are the largest publishers:

The numbers get surprisingly high here in some places:

It’s nearly 50% for Roberts Brothers; that might even be low, since they seem (from Wikipedia, I’m ashamed to admit) to have built their success on Little Women, and generally capitalized on the market that opened up.

I thought Dodd Mead was largely the education market, but wikipedia has no sign of that. Why did one mass-market publisher would publish about 1/3 women, while putnam or macmillan publish only about 1/8?

Houghton Mifflin and Little Brown both get above 20%: this probably has to do largely with the predominance of fiction (remember the PZs above), but there might be other differences as well.

Grosset Dunlap is largely the children’s market: that’s clearly a confounding factor on a lot of these statistics.

Among the low percentages:

The government printing office is not surprising, but worth remembering.

T.T. Clark is largely religious materials, I believe.

The university presses (U of Chicago, the Clarendon press at Oxford) are among the lowest. Yet another strike against the universities.

That’s the general outline of gender patterns from library book metadata in the data I have. One thing I’d like to do, but can’t with my current data, is look at whether individual libraries seem to have strongly discriminatory patterns compared to others.

If I were to draw a preliminary conclusion, it might be: established institutions–the state, the universities–seem to most strongly suppress women, presumably because there are more hurdles to jump. In certain areas, things have changed. In others, they haven’t–I ran some of this on the ArXiv author lists, and the 10-15% figures hold in the sciences. There’s no reason to think that the same massively distortionary effects aren’t still going on in academia, particularly on behalf or against social structures in addition to gender.

Keep in mind: women are the only discriminated-against group that we can pull out of library catalogs, but hardly the only ones in the 19th century. Surnames might get ethnicities–I haven’t had much luck with that–but race and class are virtually impenetrable. I suspect that access to print is at least as strongly skewed by income and race as it is by gender. I don’t think–I have to write this up at greater length–it makes any sense to not use libraries as they are not “representative.” They are what they are–libraries are interesting. Everything that anyone ever said would be interesting, too. We have one of these: we’ll never have the other.

Comments:

Awesome stuff, and I’m confident that this is …

Anonymous - May 3, 2012

Awesome stuff, and I’m confident that this is only the beginning of what we can get out of broad gender classification of metadata.

Two questions. 1) Why do you think people haven’t done this before? Didn’t require digitized text, just metadata – which we’ve had. My guess would be that error tolerances have been set too low. [“And although the data won’t be perfect, I can’t emphasize the degree to which this doesn’t matter for the sorts of questions that can usefully be asked of it.”]

Will you at some point make your gender classification public? A list of imputed genders paired to standard volume identifiers and/or author names would do it.

I don’t think there’s any rush here: you should feel free to actually publish some results on paper before making that data public. But in the long run, there’s obviously a huge potential here for further work.

1) (With the caveat that maybe it has, in various …

Ben - May 3, 2012

(With the caveat that maybe it has, in various places): part of the reason is error tolerances, definitely, and the confusion of imprecision with bias that humanists always bring up against data. Part of it is division of labor–this is more a librarian’s task than a historian’s, but librarians are rightfully wary of doing machine-classification. And part is that it may not be that useful: I don’t have a clever argument I can build around this data at the moment (and indeed, I wouldn’t have done it if I wasn’t headed towards full-text comparisons with it), and there’s not really a venue for ‘ fun facts about author genders ’. Particularly because women’s studies is frequently on the individualist side of the structure/agency divide.

For 2) Most of that should be in the file I linked, as long as it stays up. If I could pull together a real publishing agenda on this, I’d probably run with it. We’ll see. I don’t totally see a path to pull this from facts to arguments, but maybe that comes.

ID may be on the blink, but this is Ted. I think …

Anonymous - May 3, 2012

ID may be on the blink, but this is Ted.

I think the kind of information you’re seeing about presses is already pretty interesting. Not to mention the trajectory of the curve in your first illustration. I can’t believe that dip is real – but if it were real, that would require a pretty big argument.

I’m also very confident that the full-text comparisons you’re working up are going to be interesting. There are some really big questions that can be asked. I’m not even going to say more than that, because I figure you’re already working on it. Cheers!

I’ll say only I’m weirdly confident in tha…

Ben - May 3, 2012

I’ll say only I’m weirdly confident in that dip, although there are all sorts of reasons to suspect the data (particularly since so much of public-domain stuff is governmental. Pages 16-17 of this NSF report (pdf) give the gory details, but basically–pretty much every field experienced a 25-50% drop in the percentage of female doctorates from 1920 to 1960, in a manner only partly attributable (I believe) to the GI bill.

If ever munge in that Harvard Library metadata, it would be easy to check for sure.

LibraryThing has done some work on identifying aut…

Andrew Gray - Jun 4, 2012

LibraryThing has done some work on identifying author genders, as well, as part of their “Common Knowledge data - I don’t know how easy it is to extract, but apparently it’s been manually recorded for ~400,000 authors..

I have two iTunes libraries, one on my mother’…

Unknown - Feb 5, 2013

I have two iTunes libraries, one on my mother’s computer (that I used to share with her) and a new one on my own computer. Both libraries contain a significant number of songs. Some purchased, some from CDs. I cannot locate all of the CDs from my original iTunes, and would prefer to transfer the music in one easy step. Is this possible?

phlebotomy schools in NV

nice info

Anonymous - Apr 4, 2014

nice info Obat Aborsi | Obat Bius